Many children are so sheltered that they have not come into contact with real brutality. They learn it from comic books. Many others have had some contact with brutality, but not to a comic-book degree. If they have a revulsion against it, crime comics turn this revulsion into indifference. If they have a subconscious liking for it, comic books will reinforce it, give it form by teaching appropriate methods and furnish the rationalization that it is what every "big shot" does.

The variety of different kinds of brutality described and depicted in detail is enormous. Children have told me graphically about daydreams induced by them. Brutality in fantasy creates brutality in fact. Children's games have become more brutal in recent years and there is no doubt that one factor involved in this is the brutalizing effect of children's comics.

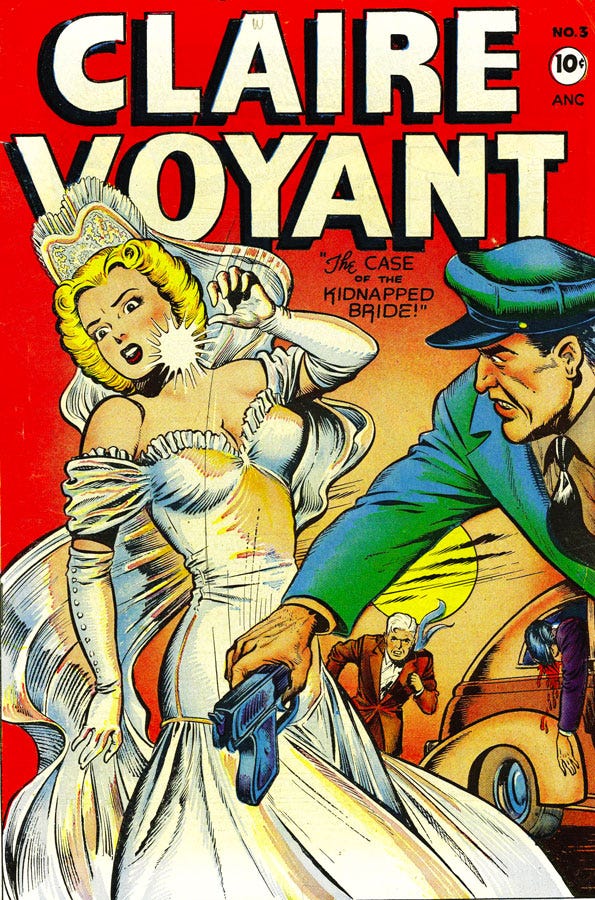

Claire Voyant #3 (Leader, 1947). Art by Jack Kamen. (Mentioned in Love and Death.)

An eight-year-old boy was examined and treated because he "wakes up at night scared." His Rorschach Test showed that he was concerned with Superman kind of things and with supernatural things. A good bit of blood in the pictures. "The kids around the block," he told us, "have millions of comic books. In school there is a gang, they are littler than me. Once I was walking to school. They sneaked behind me and they held my hands behind my back."

“Once the whole gang knocked a girl's head against the wall. They jabbed a needle into her lip. They kept jabbing it in. Once a boy played sticking a penknife into my back."

A Lafargue social worker investigated the case of an eleven-year-old boy who "played" with a boy several years younger. He put a rope around his neck, drawing it so tight that his neck became swollen, and the little boy almost strangled. His father happened to catch them and was able to prevent the incident from turning into a catastrophe. About a month later the eleven-year-old beat the younger child so that his mouth was all bloody. He did not know that one should not hit a younger and smaller boy. What he did know was that this sort of thing was done in innumerable comic-book stories about murders and robberies.

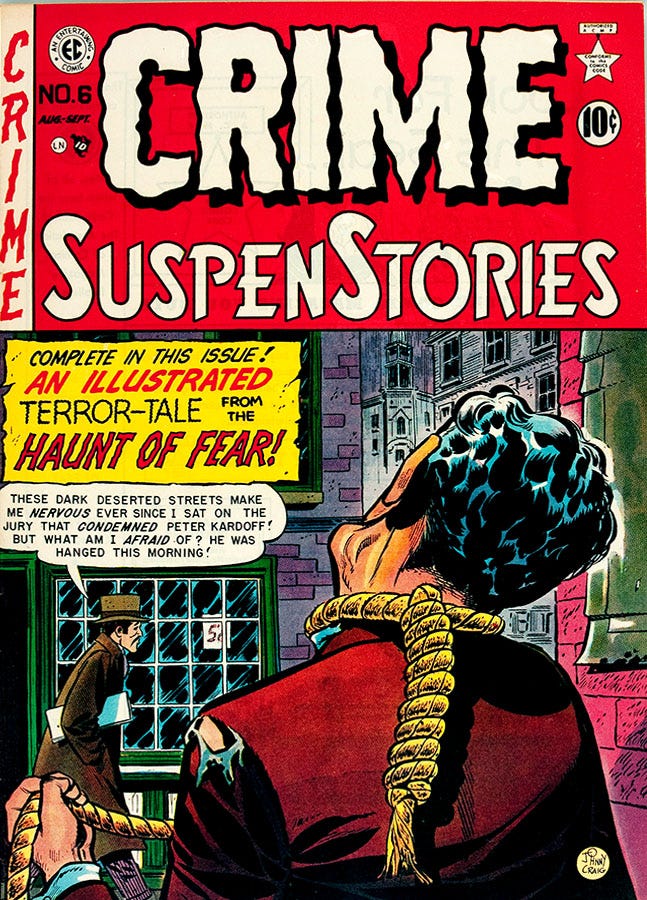

Crime SuspenStories #6 (EC, 1951). Art by Johnny Craig.

Realistic games about torture, unknown fifteen years ago, are now common among children. To indicate the blood which they see so often in crime comics they use catchup [sic] or lipstick. A boy of four and a girl of five were playing with a three-year-old boy. With a vicious look on her face the girl took hold of the younger boy and said, "Let's torture him!" Then she pushed him against the wall and marked him up with lipstick and said, "That is all blood!" One must know children's games to understand their minds, and one must know comic books to understand the games.

Violent games may be harmless enough, but only a hairline divides them from the acts of petty vandalism and destructiveness which have so increased in recent years. Camp counselors have told me that with regard to some particularly destructive and ingenious schemes the inspiration came directly from comic books brought to the camp in plentiful numbers by the parents on Sundays.

The act most characteristic of the brutal attitude portrayed by comic books is to smack a girl in the face with your hand. Whatever else may happen, afterwards, no man is ever blamed for this. On the contrary, such behavior is glamorized as big-shot stuff in the context and enhances the strength and prestige of the boy or man who does it.

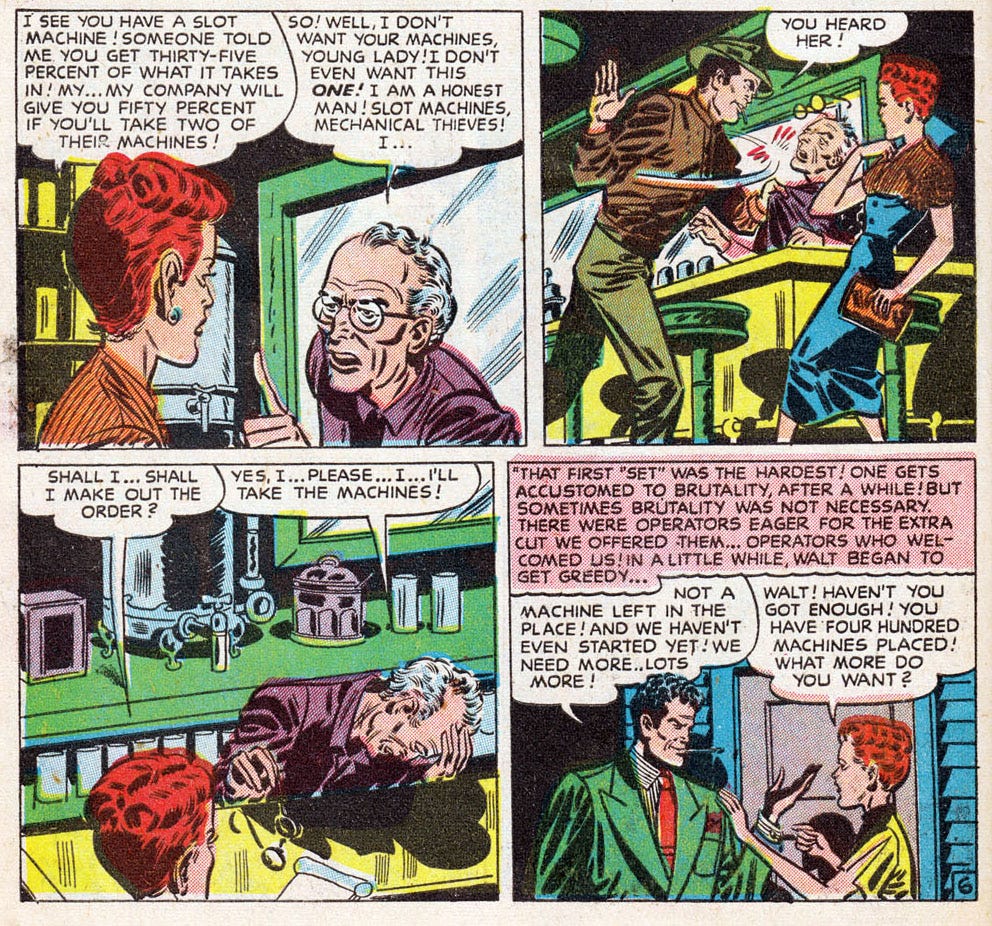

Justice Traps the Guilty #v3 #1 (13) (Prize, 1947). Art by George Gregg.

In a comic book Authorized by the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers this lesson is driven home. A young girl is being initiated as a confederate into the slot-machine protection racket. She sees how her friend beats up an old man, knocks off his glasses, etc. At first, she does not like it. But later, after she had seen such brutal treatment repeated as routine in the racket, she says: "One gets accustomed to brutality after a while!" That is one instance where I agree with a comic-book character.

In another comic book the murderer says to his victim: "I think I'll give it to yuh in the belly! Yuh get more time to enjoy it!"

Is shooting in the stomach to inflict more pain really a natural tendency of children?

Often the ending of the stories, which is generally supposed to be moral, is an orgy of brutality like this ending of a horror comic-book story: "His body was torn to shreds, his face an unrecognizable mass of bloody and clawed flesh!"

In many comics stories there is nothing but violence. It is violence for violence's sake.

The plot: killing.

The motive: to kill.

The characterization: killer.

The end: killed.

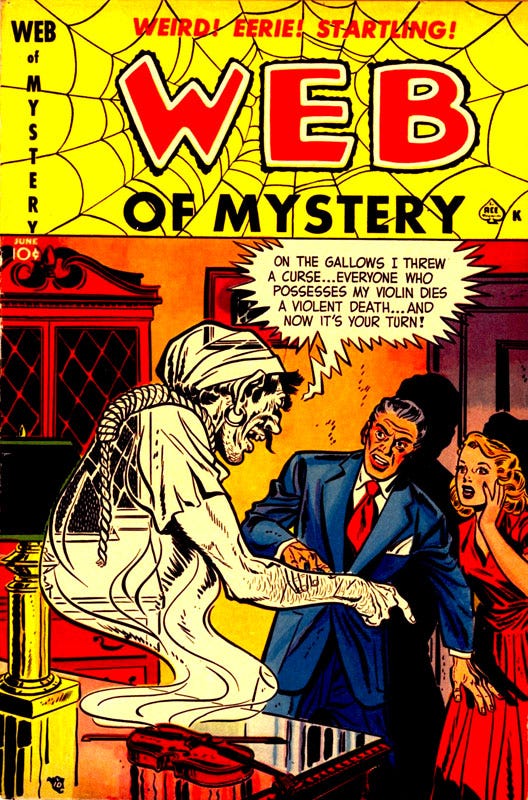

In one comic book the scientist ("mad," of course), Dr. Simon Lorch, after experimenting on himself with an elixir, has the instinct to "kill and kill again." He "flails" to death two young men whom he sees changing a tire on the road. He murders two boys he finds out camping. And so on for a week. Finally, he is killed himself.

"Strange Potion of Dr. Lorch." 1st publ in Web of Mystery #3 (Ace, June 1951).

Pencils by Mike Sekowsky. Inks by Vince Alascia.

SYNOPSIS: A potion of super-human strength changes timid Dr. Lorch into a primordial cave-man hunting for flesh and killing people in his way. In the end Dr. Lorch finds his master in confronting a circus gorilla. The potion is destroyed.

FRED’S VIDEO COLLECTION

Pressure Point (1962) was directed and co-written by Hubert Cornfield. It’s about a prison psychiatrist treating an American Nazi sympathizer during World War II.

Sidney Poitier believed that Stanley Kramer cast him for political reasons, i.e. placing a black man in a role that wasn't race-specific, believing that it was more important than any box office. In his autobiography, he noted "obviously a picture about a black psychiatrist treating white patients was not the kind of sure-fire package that would send audiences rushing into theatres across the country [in 1962]. But Kramer had other gods to serve, and he was faithful to them."