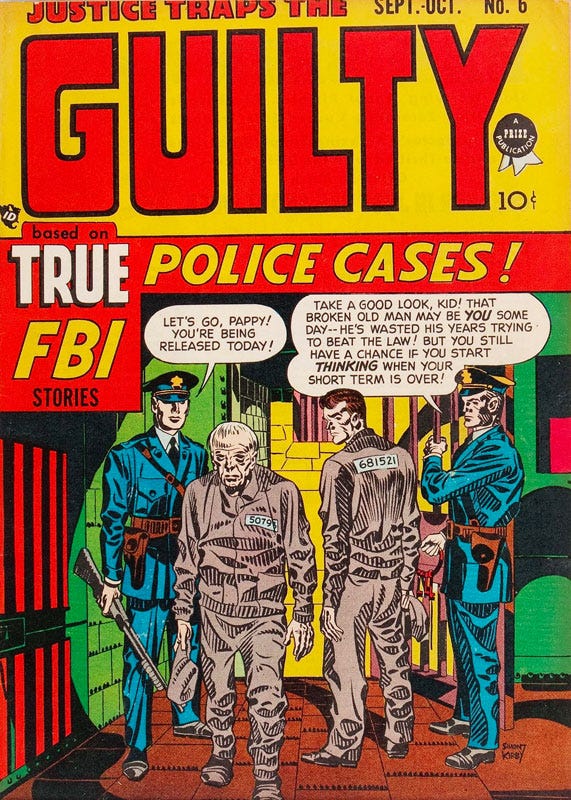

Design for Delinquency

The Contribution of Crime Comic Books to Juvenile Delinquency

"'We do not know the cause.' Is it not absurd to think of 'the' cause? Should we, over that, neglect the facts we have?"

- Adolf Meyer, M.D.

The case was handled with the utmost secrecy. "The F.B.I.." the papers later proudly reported, "took no chances." Over twenty Federal agents armed with the latest weapons were strategically posted among bushes and along the road, ready to shoot it out with whatever violent enemies of society had sent the extortion note, with a threat to kill, to a Vanderbilt.

fn. The Vanderbilts were once the wealthiest family in America. Cornelius Vanderbilt was the richest American until his death in 1877. After that, his son William acquired his father's fortune, and was the richest American until his death in 1885. The Vanderbilts' prominence lasted until the mid-20th century, when the family's 10 great Fifth Avenue mansions were torn down, and most other Vanderbilt houses were sold or turned into museums in what has been referred to as the "Fall of the House of Vanderbilt."

They were waiting for the deadline, when the extortion money was to be handed over.

When it came, a slim schoolboy appeared from his hiding-place. In his pocket he carried a toy pistol. Quickly he was surrounded by the armed might of the United States Government which - without being aware of it - was fighting juvenile delinquency.

The boy was fifteen years old, was questioned three hours, was found "guilty of juvenile delinquency" and sentenced to six years in a Federal correction institution where, in the judge's words, he would be able "to adjust himself satisfactorily."

This is by no means an isolated instance. The fight of the armed might of the law against children has become routine. One Sunday night a patrolman in New Jersey reported to police headquarters that he had seen some suspicious movement in a meat market. Two squad cars sped to the scene and came to a screeching stop. Six policemen rushed out of the cars with drawn guns and surrounded the store. Then two of them entered it, ready for battle. Their quarry turned out to be - a handsome, blond, curly-headed little boy of six. His companions, who had fled when the rope snapped as they were lowering him through a skylight, were twelve and thirteen. The little boy, too young even for a juvenile delinquency charge, had started his career as a burglar at five, rewarded by his companions with a steady supply of candy and crime comic books.

In California two police cars pursued an automobile in mad chase. The car had been stolen, evidently by criminals who had previously broken into a store. As the cars were speeding along, the police fired a salvo of shots. When the car came a stop, the policemen, guns in hand, walked up to it cautiously. Huddled in the seats were - six children. The youngest was eight, the oldest thirteen.

The authorities are fighting juvenile delinquents, not juvenile delinquency. There is an enormous literature on juvenile delinquency. One might think that society hopes to exorcise it by the magic of printer's ink. It would seem that the real scientific problem is conveniently overlooked. Juvenile delinquency does not just happen, for this or that reason. It is continuously re-created by adults. So the question should be: Why do we continuously re-create it? Even more than crime, juvenile delinquency reflects the social values current in a society. Both adults and children absorb these social values in their daily lives, at home, in school, at work, and also in all the communications imparted as entertainment, instruction or propaganda through the mass media, from the printed word to television. Juvenile delinquency holds a mirror up to society and society does not like the picture there. So, it goes in for all kinds of recrimination directed at the children, including such facile high-sounding name-calling as "hysteroid personality," "hystero-compulsive personality," and "schizophrenic tendencies."

I have seen many children who drifted into delinquency through no fault or personal disorder of their own. When they wanted to extricate themselves they either had no adults to appeal to or those who were available had no help to offer. One evening at the Lafargue Clinic a thirteen-year-old boy came to see me. He was the head of a gang and, as a matter of fact, it was one that had lately been involved in a fight with a fatal shooting. I found out later that while he was in the Clinic he had two much bigger boys stationed in the corridor and at the street entrance to function as bodyguards in case a rival gang might appear.

He was much concerned: "I want to stop the bloodshed," he said. There had been some friction between his boys and some boys of another gang. At this particular moment, he told me, '~the school is the most dangerous place," for that is where the boys would meet. "I am afraid they will fight with knives. We have our own meeting-place - nobody can find it. It is in an abandoned house." He wanted some of his boys to stay away from school for a while and during that period wanted to arrange a real peace. "But," he said, "it can't be done because the truant officer gets you and, of course, you can't explain it to him, and you can't tell it to the teacher, and you can't tell it to the police, and you can't tell it to your parents."

When we checked the situation later, we found that what he said was precisely true. Had any adult in authority been as earnestly concerned about these gang fights as this boy was, they could have been stopped. The secret meeting-house, incidentally, was stacked full of textbooks for violent “fighting-crime” comics.

Fred’s novel idea

More stuff happens this week… and it’s beginning to look a lot like an actual story.

The Principle of Hope continues…

The Not-Yet-Conscious, Not-Yet-Become, although it fulfills the meaning of all men and the horizon of all being, has not even broken through as a word, let alone as a concept. This blossoming field of questions lies almost speechless in previous philosophy. Forward dreaming, as Lenin says, was not reflected on, was only touched on sporadically, did not attain the concept appropriate to it. Until Marx, expectation and what is expected, the former in the subject, the latter in the object, the oncoming as a whole did not take on a global dimension, in which it could find a place, let alone a central one.